In the world of fine jewelry, wood has emerged as a captivating material, prized for its organic warmth, unique grain patterns, and sustainable appeal. However, its integration into high-end accessories has historically been hampered by a fundamental challenge: its inherent instability when confronted with significant environmental fluctuations. This is not a minor inconvenience but the central obstacle preventing wider adoption. The very cellular structure of wood, a natural hygroscopic material, causes it to expand with moisture absorption and contract upon drying. In regions with vast differences in climate, particularly between the humid tropics and arid northern zones, or even within a single continent like North America, this constant movement can lead to cracking, warping, and the failure of adhesive bonds or inlays. Addressing this instability is not merely a technical exercise; it is the key to unlocking wood's full potential as a legitimate and durable medium for luxury jewelry design.

The core of the problem lies in wood's relationship with water. Unlike metals or plastics, wood is an anisotropic material, meaning its properties differ along its various axes. It expands and contracts most significantly tangential to the growth rings, less so radially, and minimally along its length. This differential movement creates immense internal stresses. When a piece of jewelry crafted in the consistent humidity of a Singapore workshop travels to the dry, heated indoors of a Canadian winter, it undergoes a rapid and violent expulsion of moisture. If the design does not accommodate this movement, the wood will fight against its constraints—be it a metal setting, a resin fill, or a glued seam—inevitably leading to failure. The goal, therefore, is not to make the wood impervious to its environment, an impossible task, but to design around its natural behavior, allowing it to breathe and move without compromising the structural or aesthetic integrity of the piece.

Material selection forms the first and most critical line of defense. Not all woods are created equal in the face of humidity. Designers and engineers are increasingly turning to dense, fine-grained species known for their dimensional stability. Lignum Vitae, one of the densest woods on earth, has an natural oil content that makes it highly resistant to moisture uptake. Similarly, African Blackwood and Cocobolo possess natural oils and resins that stabilize their structure. Seasoned Ebony and certain old-growth Teak varieties also exhibit superior stability due to their tight grain and density. The process of selection is now more scientific than ever, with artisans considering not just the Janka hardness scale but also detailed shrinkage coefficients—the precise percentage a wood will shrink radially, tangentially, and volumetrically as it dries. Choosing a wood with a low and balanced shrinkage coefficient is paramount for any piece intended for a global clientele.

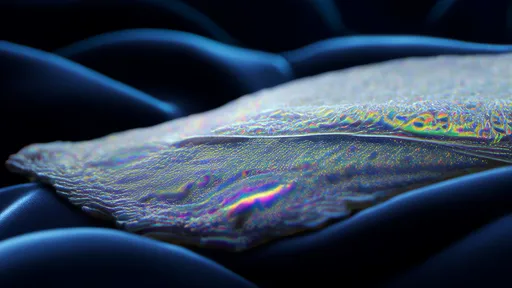

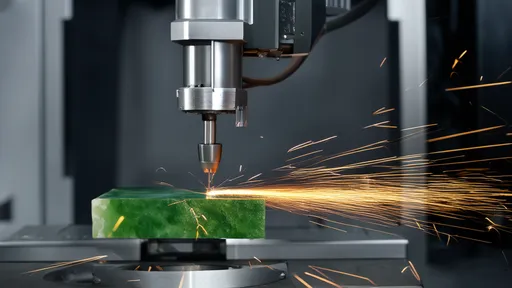

Beyond selecting the right species, the treatment and preparation of the wood itself are where modern technology makes a profound impact. Traditional kiln-drying is often insufficient for the rigorous demands of jewelry. Instead, many top-tier artisans employ a process of stabilization. This involves placing meticulously dried wood blanks in a vacuum chamber. The vacuum pulls the air from the wood's cellular pores, which are then infused with a stabilizing resin monomer. When cured, typically with heat, this resin hardens within the wood, effectively replacing the water-reactive cellulose with a stable, plastic-like polymer. The result is a material that retains the exact look and feel of wood but is rendered impervious to moisture, eliminating virtually all expansion and contraction. This process transforms even relatively unstable but beautiful woods into viable materials, opening up a much broader palette for designers.

However, stabilization is not always desirable for purists who seek the authentic tactile sensation of untreated wood. For these pieces, ingenious mechanical design becomes the solution. The philosophy shifts from restricting movement to accommodating it. This can involve designing floating elements where the wood is not rigidly glued to a metal backing but is instead held in place by strategic mechanical anchors that allow for lateral movement. Another technique is the use of expansion joints or deliberate gaps filled with flexible materials like silicone or specialized elastomers that compress and expand with the wood. The design of inlays also evolves; instead of embedding wood directly into a cavity in metal, designers might create a "frame and panel" system, akin to fine furniture, where the wood panel is free to move within a secure metal frame, preventing pressure buildup.

The marriage of wood and metal is a classic combination in jewelry, but it is also a potential point of failure due to their vastly different thermal expansion rates. Solving this requires a metallurgist's touch. Selecting metals with expansion coefficients that more closely align with the chosen wood can mitigate stress. Titanium and certain specialized alloys are increasingly favored for this reason. Furthermore, the method of attachment is critical. Rivets, prongs, and minimalistic spot welds allow for more flexibility than a continuous bezel or a full sheet of adhesive. The application of adhesive itself is re-engineered; high-end flexible epoxies designed for marine or aerospace applications, which can withstand constant cyclic stress, replace standard jewelry glues. The bond is designed to be elastic, bending with the movement rather than resisting it unto breaking.

For the consumer, understanding and care are the final components of this stability equation. Jewelry houses tackling this challenge are investing in educating their clients. A piece of wooden jewelry is a living object in a way that a gold ring is not. This education involves proper care guidelines: storing pieces in stable environments away from rapid temperature changes (like radiators or car dashboards), using protective cases with humidity-regulating packets, and regular, light maintenance with appropriate oils that hydrate the wood without oversaturating it. This transforms the ownership experience from one of mere possession to one of stewardship, deepening the connection between the wearer and the natural material. The narrative shifts from a product's fragility to its unique, evolving character.

The successful creation of wooden jewelry capable of enduring extreme climatic shifts represents a beautiful synergy between respect for natural materials and the application of cutting-edge science. It is a field where the artisan's intuition meets the engineer's precision. Through meticulous material science, advanced stabilization techniques, intelligent mechanical design, and client education, the industry is steadily overcoming the historical barriers. The result is a new generation of wooden jewelry that is not only stunningly beautiful but also robust and travel-ready. This progress ensures that the earthy elegance of wood can be confidently worn and cherished anywhere on the planet, from the humid equatorial regions to the arid northern climates, truly making it a material for a global audience.

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025